There is a continuing trend in search term cases: You do not see judges discussing experts and Federal Rules of Evidence 702. Now, perhaps this is just in cases where custodian names or simple search terms were at issue, such as William A. Gross Constr. Assocs. v. Am. Mfrs. Mut. Ins. Co., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22903 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 19, 2009) and Asarco, Inc. v. United States EPA, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 37182 (D.D.C. Apr. 28, 2009).

There is a continuing trend in search term cases: You do not see judges discussing experts and Federal Rules of Evidence 702. Now, perhaps this is just in cases where custodian names or simple search terms were at issue, such as William A. Gross Constr. Assocs. v. Am. Mfrs. Mut. Ins. Co., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22903 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 19, 2009) and Asarco, Inc. v. United States EPA, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 37182 (D.D.C. Apr. 28, 2009).

The main focus of Curtis v. Alcoa, Inc.,2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 71581 (E.D. Tenn. Mar. 27, 2009) was whether specific discovery was protected by the attorney-client privilege (a great exercise for law students taking Evidence). A secondary focus of the opinion was a motion to compel an additional ESI search with revised keywords. Curtis, 38-39.

The Plaintiffs’ wanted seven additional keyword combinations run against nine custodians (which included such terms as “Enron/OPEB” and “Sarbanes-Oxley/OPEB”). Curtis, 38.

The Defendants’ claimed the searches had been run against seven of the nine custodians. Agreeing to run the searches over the additional two custodians seemed to be a non-issue. Curtis, 39.

The Court ordered the Defendants, if it had not already been done, to run the designated searches with the revised key words on the nine custodians and indentify the responsive search results. Curtis, 39.

Are the Angels Treading Lightly?

“…for lawyers and judges to dare opine that a certain search term or terms would be more likely to produce information than the terms that were used is truly to go where angels fear to tread.”

Magistrate Judge Facciola, United States v. O’Keefe, No. 06-CR-249, 2008 WL 44972, 8 (D.D.C. Feb. 18, 2008).

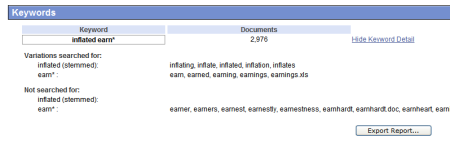

I think there is a rule of thumb with search terms: If you will need to prove the responsiveness of your searches or whether forensic analysis was performed, you will see an expert report or an evidentiary hearing.

I think there is a rule of thumb with search terms: If you will need to prove the responsiveness of your searches or whether forensic analysis was performed, you will see an expert report or an evidentiary hearing.

Cases such as Covad Communs. Co. v. Revonet, Inc., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 47841 (D.D.C. May 27, 2009); United States v. O’Keefe, No. 06-CR-249, 2008 WL 44972 (D.D.C. Feb. 18, 2008 ); and Equity Analytics, LLC v Lundin, 248 F.R.D. 331 (D.D.C. 2008 ) fall into this group.

On the other side of the spectrum, courts are narrowing search terms to specific individuals (such as Dunkin’ Donuts Franchised Rests. LLC v. Grand Cent. Donuts, Inc., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 52261 (E.D.N.Y. June 19, 2009)) or variations of custodian names (William A. Gross Constr. Assocs. v. Am. Mfrs. Mut. Ins. Co.). These situations require active meet and confers and interviews with custodians so search terms are not in designed wildly without reason.

The key to both is attorneys proving their search methodology with affidavits or experts being deposed where search terms must be defended. In the first instance, software tools that generate search term reports will likely be affidavit exhibits. Both situations will probably require lawyers working with an outside vendor or in-house e-discovery professions to ensure search term responsiveness.