“OCR, while perhaps not absolutely necessary to litigation, is a tool that greatly decreases the time and effort counsel must invest in searching and examining documents. Presumably, each party would perform the OCR process in a cost-effective manner to minimize their costs. Requiring the parties to incur this cost, when the OCR process is likely to streamline the discovery process and reduce the chance that either side will employ tactics designed to hide relevant information in a mountain of difficult-to-search documents is neither unreasonable nor burdensome.”

United States District Judge Ron Clark

Proctor & Gamble and S.C. Johnson & Son are in litigation over products with sales in the millions. The parties were ordered to provide the Court with cost estimates to produce paper documents as TIFFs with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) so the static images would be searchable. P&G v. S.C., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13190 (E.D. Tex. Feb. 19, 2009).

Thankfully, this is not a case where the parties and the Court were discussing OCR on electronically stored information like email, Excel files or other native files. ESI is already ready searchable and does not need to be OCR-ed. P&G v. S.C., 3.

The Defendant, S.C. Johnson, claimed the OCR process would cost over $200,000. Additionally, they took the position they would not use the OCR and requested cost shifting. The Plaintiff estimated the cost to be around .03 cents a page. P&G v. S.C., 4. Needless to say, the Court had a tough time believing that in our age of ESI such a large volume of the S.C. Johnson discovery would be in paper form needing to be OCR-ed to the tune of $200,000. P&G v. S.C., 4.

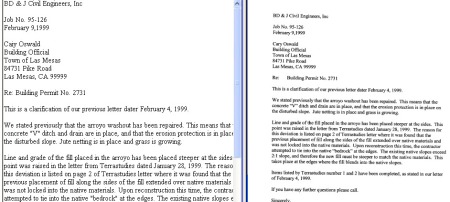

On the left, OCR text in CT Summation iBlaze. On the right, the static TIFF image of the same document.

The Court applied the 7 factors from Zubulake in considering the Defendant’s claims for cost shifting. Those 7 factors include:

(1) The extent to which the request was specifically tailored to discover relevant information;

(2) The availability of such information from other sources;

(3) The total cost of production, when compared to the amount in controversy;

(4) The total cost of production, when compared to the resources available to each party;

(5) The relative ability of each party to control costs and the incentive to do so;

(6) The importance of the issues at stake in the litigation; and

(7) The relative benefits to the parties of obtaining the information. P&G v. S.C., 4-5, citing Zubulake, 217 F.R.D. at 322

The Court quickly found against cost-shifting for the OCR process based on the following:

There was no showing that the request was for non-relevant information nor reasonably likely to lead to the discovery of admissible information.

No showing that the documents were obtainable from other sources.

The parties’ respective litigation budgets were estimated to be several million dollars apiece. P&G v. S.C. 6-7.

The Court did not order cost-shifting. Both parties were ordered to produce paper documents as searchable TIFFs with OCR. The Court’s recognition of utilizing OCR in discovery was thoughtful and a solid acknowledgement that technology can help reduce discovery costs.